Problem-Focused and User-Centered Designs in Research and Practice

By Jessie Tobin, Lisa Yu, & Kristen C. Wilcox

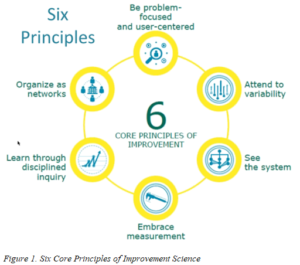

In this blog, we highlight one of the six principles of Improvement Science; being problem-focused and user-centered. We connect it to NYKids improvement work and research with a few suggested strategies and links to tools for others to engage in this principle in their practice.

The essence of this principle is intuitive: when a change is proposed, it ought to be rooted in users’ experiences and understandings of problems in their own contexts.

The essence of this principle is intuitive: when a change is proposed, it ought to be rooted in users’ experiences and understandings of problems in their own contexts.

In research, a similar idea undergirds methods aligned with “interpretivist” frameworks that are essentially focused on discovering and then describing how people experience phenomena in their lives.

For the most recent NYKids College and Career Readiness Study, our research team sought to discover and describe how students themselves experience high school. These experiences include where and when they encounter problems and what or who helped them along their way.

While the intended outcomes of improvement work and research studies differ, ways of coming to understand how people experience problems matter for research and practice. Tools that researchers and practicing professionals use to understand users’ experiences share some commonalities.

Problem-Focused and User-Centered Strategies

Here we outline two recommended strategies and provide some examples from our own research on how to follow through with the principle of being problem-focused and user-centered.

#1 Have a clear purpose

A critical question undergirding this recommendation is: Why do I want to get this information and not focus on something else? To this end and to make clear our purpose when we design our studies at NYKids, we spend time talking with our school partners. These participants are “users” themselves and closest to the most pressing problems in schools and classrooms. In our most recent NYKids College and Career Readiness Student Study, we first discussed ideas about the focus of our study with our Advisory Board members. They made clear that it was critically important for us to gather students’ perspectives on college and career readiness as a follow up to our initial study investigating district and school leaders’, teachers’, and support staff perspectives.

As a start, they pointed us in the direction of learning more about how to encourage student agency. The Board was also concerned about equity and social justice issues from kids’ perspectives.

Next, we reviewed different research databases on related lines of research, including our own prior NYKids’ studies. As outlined in our Methods and Procedures report (coming soon to our Resources page), we identified several themes we knew we wanted to inquire about in our interviews and focus groups with kids. These then gave us precision about what was within and outside the scope of our inquiry.

#2 Provide opportunities for informants to describe and explain their experiences

A critical question undergirding this recommendation is: Am I leading a response or opening up a topic for people to inform me?

One of the major goals of conducting interviews and focus groups is to gain a better understanding of informants’ feelings and experiences. Here it is important to never assume the answer and use frequent follow-up questions like “Can you tell me more about that?” or “Can you provide an example?” Some teacher-researchers have found that sometimes it is necessary to rephrase a question or give more explanations around it. This is particularly the case when children and young people look confused or are just hesitant to respond when they are talking with an adult.

One of our NYKids interview questions, for example, asked students to describe a time when they felt that “something related specifically to them was taken into consideration in school.” Since this question may be too abstract for some adolescents, our researchers used our own personal experiences as examples for clarification. This clarification also provides an opportunity for both interviewers and interviewees to get to know each other and build up a mutual trust. We also supplemented our questions with invitations for study participants to draw timelines and maps in relation to our questions.

One of our NYKids interview questions, for example, asked students to describe a time when they felt that “something related specifically to them was taken into consideration in school.” Since this question may be too abstract for some adolescents, our researchers used our own personal experiences as examples for clarification. This clarification also provides an opportunity for both interviewers and interviewees to get to know each other and build up a mutual trust. We also supplemented our questions with invitations for study participants to draw timelines and maps in relation to our questions.

Tools of the Trade

Two tools to get a user-centered perspective are highlighted below:

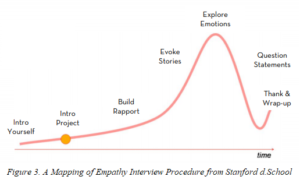

An Empathy Interview is a human-centered approach to understand the feelings and experiences of others. It is also popular among those engaging in Improvement Science. It can help adults gain a deeper understanding of students’ perspectives and needs to in turn provide better services and support for them. On a practical level, it has been reported that empathy interviews enable students to “demonstrate their proficiency” and “receive immediate feedback” from their teachers.

An Empathy Interview is a human-centered approach to understand the feelings and experiences of others. It is also popular among those engaging in Improvement Science. It can help adults gain a deeper understanding of students’ perspectives and needs to in turn provide better services and support for them. On a practical level, it has been reported that empathy interviews enable students to “demonstrate their proficiency” and “receive immediate feedback” from their teachers.

Shadowing a student is a process of following and observing a student (one day or longer) to understand what the student feels and experiences. It offers school leaders and teachers opportunities to see school through their students’ eyes, especially those students who may be marginalized in some way. Shadowing a student can be used as a powerful tool for educators to gain insights from their students and eventually make improvement at their schools.

Find more information on the NYKids Resource page on how to take a problem-focused and user-centered approach. You can also view our research results from the College and Career Readiness studies for more insights. As always, we welcome your feedback and suggestions at nykids@albany.edu and invite your inquiries if you have need for research or school improvement support.