The Six Principles of Improvement Science Unpacked and Showing Results

By Kristen C. Wilcox

Whether tackling the challenge of differentiating literacy instruction to suit the diverse needs of children in elementary schools or engaging teens at risk of dropping out of high school, the kinds of problems educators face are as complex as they come. Drawing from lessons learned in other sectors, educators are increasingly looking for ways to address longstanding outcome disparities for children and youth growing up in poverty, as well as for those from diverse ethnic, cultural, and linguistic backgrounds.

Improvement Science and Continuous Improvement: Why Now?

A recent Ed Week article on the Every Student Succeeds Act points to why Improvement Science is so relevant now, stating: “Continuous improvement has quickly become a buzzword in K-12 policy and practice as states, districts, and schools strive for systemic, long-term gains in student achievement, instead of looking for the next, shiniest silver bullet”.

What is Improvement Science and How does it Help Avoid the Pitfalls of Silver Bullets?

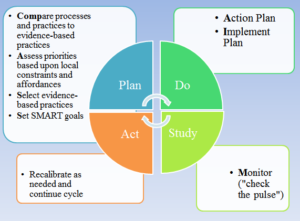

Improvement Science is prefaced on the idea that for individuals and organizations to improve, “failing forward” is often necessary and should be embraced. As an essential part of organizational learning, emphasis is placed on “disciplined inquiry”—of carefully monitoring the impact of changes through plan, do, study, and act cycles (i.e. PDSAs).

The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching has offered guidance to others on the core Six Principles of Improvement Science.

Principle 1. Make the work problem-specific and user-centered1.

It starts with a single question: “What specifically is the problem we are trying to solve?” It enlivens a co-development orientation: engage key participants early and often.

Principle 2. Variation2 in performance is the core problem to address.

The critical issue is not what works, but rather what works, for whom and under what set of conditions. Aim to advance efficacy reliably at scale.

Principle 3. See the system3 that produces the current outcomes.

It is hard to improve what you do not fully understand. Go and see how local conditions shape work processes4. Make your hypotheses5 for change public and clear.

Principle 4. We cannot improve at scale what we cannot measure6.

Embed measures of key outcomes and processes to track if change is an improvement. We intervene in complex organizations. Anticipate unintended consequences and measure these too.

Principle 5. Anchor practice improvement in disciplined inquiry.

Engage rapid cycles of Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA)7 to learn fast, fail fast, and improve quickly. That failures may occur is not the problem; that we fail to learn from them is.

Principle 6. Accelerate improvements through networked communities8.

Embrace the wisdom of crowds. We can accomplish more together than even the best of us can accomplish alone.

Six Core Principles of Improvement Science

NYKids Using Improvement Science Processes and Tools Shows Results

NYKids, rooted in the mission to inform (through interactive databases), inspire (through research on odds-beating schools), and improve (outcomes for children through dissemination and use of research) began to turn to Improvement Science as a way to tackle some of the complex problems plaguing schools and districts in 2010. Since then the NYKids team along with partners from the Capital Area School Development Association have offered direct assistance to school leaders and teams in taking up these principles.

By melding NYKids’ research on odds-beating schools and Improvement Science principles, NYKids developed the COMPASS-AIM process (an acronym for the multiple steps of an improvement science-based process). COMPASS-AIM follows the logic of the Six Principles of Improvement Science by guiding educators through the following steps:

- COMParing practices to best practices and comparing outcomes across subgroups;

- Assessing priorities in light of local needs and resources;

- Selecting levers to improvement drawing on research in odds-beating as well as other schools;

- Setting SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound) goals accompanied by near term aims;

- Action planning, Implementing an action plan, and Monitoring improvement

COMPASS Process Mapped to PDSA

COMPASS Process Mapped to PDSA

All the while NYKids and CASDA faculty encourage COMPASS teams to draw upon the power of networks (intra-school and inter-school) to accelerate learning.

In contrast to typical strategic planning or other types of team work, “COMPASS” teams engage in a process of goal and aim setting rooted in the Improvement Science principle of “seeing the system that produces the outcomes”, continuously measuring progress, and making adjustments accordingly.

NYKids’ research examining the effects of engaging Improvement Science-based processes and tools via COMPASS in dozens of schools has revealed growth in educators’ will and capacity to engage in continuous improvement efforts and, in some cases, with demonstrable improved student outcomes as well.

A Case in Point: Arongen Elementary

Partnering with Arongen Elementary school (a relatively large suburban elementary school in upstate New York), NYKids distributed its baseline system self-assessment that helps educators see how their school compares with odds-beating schools.

After reviewing the self-assessment results and assessing their priorities based on local needs and resources, Arongen COMPASS team members identified scheduling as a key lever to improvement. One teacher explained: “In classrooms, the providers are running around constantly… we don’t have time to discuss with each other what we’re doing”.

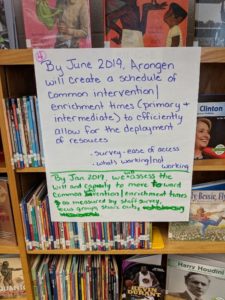

Team members then agreed upon specific aims to create a common intervention and enrichment schedule to address this problem. By following the COMPASS protocols built from Improvement Science, as well as NYKids and other research on intervention and enrichment, team members articulated their overarching goals and aims ensuring they were time-bound and included methods to gather data on progress.

Arongen Team-developed school-wide improvement goal

At mid-year, Arongen team members were asked to reflect on their experiences. Overwhelmingly, they commented about the powerful influence of this work as it advanced their collective efficacy to make school improvements.

As one respondent put it, “Working with COMPASS & NYKids has allowed our group to focus on the needs of the school with research-based resources.” Another explained, “The team from UAlbany is so ready to support and help. Our building feels comfort from the higher-ed institution and I appreciate the connectedness!”

In summing up how this school improvement approach differed from others, the principal reflected … “there’s never a next step connected to it [other school improvement professional development]. It’s just a very finite approach and this had a fluidity that is much, much better.”

How is This Approach Different from Other Approaches to Improvement?

Improvement Science differs from other improvement approaches in that it addresses two major obstacles to improvement:

- Solutionitis– the propensity to jump quickly on a solution before fully understanding the exact problem to be solved

- Groupthink– a shared belief that results in an incomplete analysis of the problem to be addressed and full consideration of the potential problem-solving alternatives

Instead it focuses on “User-centered designs”— designs fit for purpose relying upon the insights of front-line workers’ experiences in understanding problems and will to engage in innovation

As “continuous improvement” continues to gain traction as a buzz-word in the education sector, Improvement Science developed over years in other sectors, provides insight into ways to leverage the knowledge and experience of educational professionals and bring about system-wide improvements.

For more tools and resources for continuous system improvement see The Systems Center and delve into the tools and resources at NYKids.