Supporting Asian American Students and Families to Combat Anti-Asian Violence

By Lisa Yu

Since last weekend, thousands of protestors rallied to “Stop Asian Hate” around the country, calling for an end to violence against Asian Americans. According to the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism, anti-Asian hate crimes in large cities surged by 145% in 2020 as a result of fear evoked by the COVID-19 pandemic. The increased verbal assaults, physical attacks, crimes, and the recent shootings in Georgia have spread fears, anger, and grief among Asian American communities. Many Asian Americans are endeavoring to raise their voices and seeking ways to fight back against anti-Asian hate.

Some changes are happening. On March 11th, two Asian congresswomen introduced a bill to expedite the review of hate crimes related to the pandemic. Some lawmakers testified in a hearing and called for a shift in public rhetoric surrounding COVID-19 on March 18. In addition to progress at the political level, some researchers have argued that the most effective way to create change is through education. It is time for educators of all backgrounds to gain a better understanding of Asian Americans, a group of people that have been historically ignored and underrepresented in this country.

Debunking the Myth of “Whiz Kids”

Model Minority is probably the most pervasive myth around Asian Americans. Meanwhile, Asian American kids are frequently described as “whiz kids” in the media – a term used to encompass children who are intelligent, obedient, hardworking, and able to succeed on their own.

The model minority stereotype is based on a narrow conception of student performance and does not consider Asian American students’ learning needs and struggles when attempting to succeed in the academic community. Some studies, though very few, have pointed out that teachers, parents, and fellow students all place high and even unrealistic academic expectations on Asian American students. Such expectations can exacerbate the stress and anxiety these students feel to perform well in school.

The model minority myth also positions Asian Americans, including those who are born and educated in America, as perpetual foreigners rather than “our fellow Americans.” How many Asian Americans who have been living in this country their entire lives are constantly complimented for their fluent English?

This misconception also leads to an identity issue among Asian American youth. It is reported that Asian American adolescents are more likely to be assimilated to mainstream culture, at the cost of waning their Asian identities, if compared to their peers from other minority groups. To disassociate themselves from “over-conformist, emotionally repressed, socially inept, and physically unattractive” characteristics, Asian American adolescents tend to manifest or pretend to show that they are not interested in math learning or have aspirations in athletics.

Engaging Asian American Families and Communities in School Activities

How can we debunk the model minority myth and acknowledge the value of Asian American cultures? Some states have taken the lead. Currently, a push to include Asian American history is taking place in California and Connecticut.

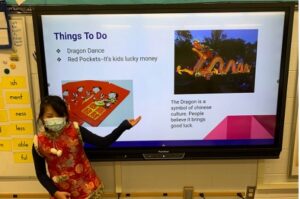

In New York, teachers in some schools are encouraged to incorporate Asian American history and culture into their existing lessons. They also find creative ways to engage Asian American families and communities in school activities. For example, Shenendehowa district – a partnered district of NYKids – offers students the opportunity to earn college credits by learning the Chinese language. This year, a Chinese American student was invited to give a presentation on the Lunar New Year in an elementary school classroom. Leaders in this district also plan to collaborate with the local Chinese communities and start a new course focused on Chinese Business Language.

A NYKids COMPASS School Bridging the Divide

Arongen Elementary School, an elementary school in the Shenendehowa district, has worked with NYKids’ COMPASS direct support in prior years. COMPASS is an acronym for Compare, Assess priorities and resources, Select levers to improvement, and Set SMART goals. The Arongen COMPASS team set out to improve the engagement of minority parents and communities in school programs and activities. Base on prior research, we know that Parental engagement is closely correlated with student educational outcomes and social-emotional well-being, particularly for those with diverse backgrounds. A key in implementation is that leaders and teachers perceive cultural diversity as an asset rather than a deficiency. School programs and activities should embrace cultural difference and meet minority families’ needs by providing language supports. Teachers also need to provide a clear clarification of the objectives and expectations of school events to parents who are probably not familiar with Western academic culture and norms for parent participation.

Without robust efforts such as those highlighted above, anti-Asian American racism will continue to exist and lead to new crimes and tragedies. The first steps are for policy makers, leaders, and educators to seek to understand the academic and social-emotional needs of Asian American students and find effective ways to communicate with their parents and communities.

For more information on parental engagement and educational equity, please visit our webpage for resources and blogs. We encourage you to sign up for our Newsletter and reach out to us with any questions you may have about NYKids’ COMPASS direct support at nykids@albany.edu.