What do Educators in Turnaround Schools Do and How Do They Do It?

By Brian D. Rhode (Interim Director of Professional Development and Lead Evaluator, Averill Park CSD) and Kristen C. Wilcox (Director of Research and Development, NYKids)

It seems fair to say that most educators strive to consistently improve student outcomes. However, in schools that are in decline or have histories of under-performance, turning around sub-optimal outcomes can be elusive. Several schools in the latest NYKids study have faced the need to turnaround their performance and have been successful in doing just that.

Two Sets of Turnaround Odds-Beaters

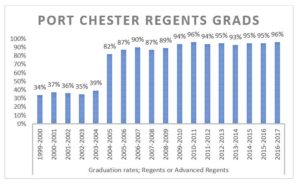

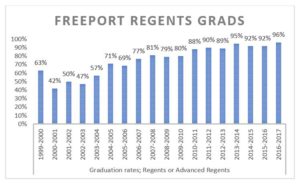

We identified two sets of turnaround schools in the pool of NYKids odds-beaters. The first set of turnarounds includes Port Chester High School and Freeport High School both of which failed to meet AYP in either ELA, math, or graduation rates for a number of years prior to being rated in good standing.

Port Chester and Freeport Adapting To Students’ Needs and Removing Barriers

One of the greatest challenges facing educators in New York State as well as around the United States is adapting their processes and practices to keep pace with rapid change in student demographics and their emotional, social, and academic needs. A defining characteristic of the approach at Port Chester relates to their willingness to adapt. Their adaptations have ranged from staffing to programming to assessment practices as well as the types of academic interventions they offer. Keeping pace with students’ (and their families’ needs) is done through the lens of their diverse experiences, prior knowledge, and current circumstances. Keeping pace with change means removing barriers in school policies (e.g., honors and AP exclusion criteria) that could hold students back from meeting their full potentials (adapted from Port Chester Case Study).

Likewise Freeport offers pathways for earning college credit while in high school with a focus on science, technology, engineering and mathematics, and opportunities for trade and technical training and experience. In response to a growing Spanish-speaking population, the district has prioritized hiring bilingual faculty and staff members while also supporting current faculty to obtain bilingual certifications. Other examples of supports include “safe zones” for LGBTQ youth and evening programs for students who must work to support their families (adapted from Freeport Case Study).

Malverne and Crown Point Changing Cultural Norms and Expectations

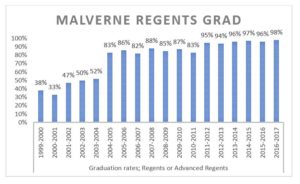

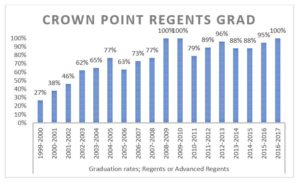

The schools in the second set demonstrated their turnaround by significantly improving the number of students receiving Regents or Advanced Regents diplomas. The odds-beaters in this set include Malverne, Crown Point, Port Chester, and Freeport. Each school met the ambitious goal of demonstrating an improvement of at least 50% in graduation rates specifically during academic years spanning 1999-2000 and 2016-2017. They also demonstrated prolonged improvement during these years.

Malverne High’s principal attributed their turnaround in part to “a change in cultural norms” and to exceptional school and district leaders as well as a dedicated cadre of passionate and capable teachers, faculty and staff. Support staff, among others, described how these “cultural” changes took shape in a number of adjustments, including raising expectations for exceeding the minimum graduation requirements, providing high school curricula in the middle school, and changing approaches toward discipline (adapted from Malverne Case Study).

Crown Point’s response to being designated by as a school in need of improvement in the 1990-s was to actively work to stop leader turnover and implement a more rigorous curriculum as well as other support programs to improve school culture and expand student opportunities (adapted from Crown Point Case Study).