New NAEd Report Highlights Need for Civic Education

By Aaron Leo and Kristen C. Wilcox

Civic education has become even more crucial in light of political and social upheavals around the world this year. To address the need to prepare young people to engage responsibly in civil society, the National Academy of Education recently conducted a webinar about their new report outlining the need for advancements in civic education and provided educators with practical guidance on how to implement effective strategies.

As the report explains, civic reasoning involves the capacity to “think through a public issue using rigorous inquiry skills and methods to weigh different points of view and examine available evidence.” Important to civic reasoning is the ability to engage in civic discourse which involves communicating with others about pressing political and social matters. The goal of civic discourse can involve finding consensus, compromises, or dissent. In NYKids latest study, students attending positive outlier schools like Malverne and Crown Point provided insight into how leaders and educators in their schools promote the skills and methods of engaging others and expressing their points of view like those recommended in the NAEd report.

Why Civics Education Matters More than Ever

The need for civics education has never been more urgent. In the last year, youth have witnessed the havoc of a global pandemic, a siege on the U.S. capitol, and increased calls by activists for social and environmental justice. Educators can help youth make sense of these topics while preparing them to address issues important to their lives.

The need for civics education has never been more urgent. In the last year, youth have witnessed the havoc of a global pandemic, a siege on the U.S. capitol, and increased calls by activists for social and environmental justice. Educators can help youth make sense of these topics while preparing them to address issues important to their lives.

Despite the growing need for civics education, the level of civic knowledge, according to the NAEd report, has “remained stagnant.” Citing two decades of low levels of student proficiency on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) Civics Assessment as just one measure, the authors call for greater attention to improving both the access to and quality of civics education across the country.

Educating for Civic Reasoning and Discourse

Using an interdisciplinary approach, chapters in the report range in perspectives including indigenous youth, youth living in the rural south, and Asian Americans. The report also addresses broad themes of structural inequality, migration and conflict while also providing concrete, practical recommendations for educators and policymakers.

Specifically, the report addresses six questions:

- What are the cognitive, social, emotional, ethical, and identity dimensions entailed in civic reasoning and discourse, and how do these dimensions evolve?

- What can we discover from research on learning and human development to cultivate competencies in civic reasoning and discourse and prepare young people as civic actors?

- What are the broader ecological contexts that influence the ability of our learning systems to support the development of these competencies?

- How do we create classroom climates and inquiry-oriented curricula that are meaningful to students’ civic learning?

- In the context of schooling, what is the role of learning across content areas in developing multiple competencies required for effective civic reasoning and discourse?

- What supports are needed in terms of policy as well as in the preparation and professional development of teachers and school administrators to design instruction for effective civic reasoning and discourse that encourages democratic values and democratic decision making?

Implications for Educators

The report authors emphasize the capacity for educators across all content areas to incorporate civics in their teaching. Several important lessons can be taken from this report:

The report authors emphasize the capacity for educators across all content areas to incorporate civics in their teaching. Several important lessons can be taken from this report:

- Learning the complex demands of civic reasoning and discourse requires attention to self-examination of implicit bias, problems of conceptual change, and weighing multiple points of view.

- Civic learning should occur in classroom climates that are conducive to student discussion and engagement. Teachers should encourage student voice and engagement by respecting and drawing on diverse student experiences.

- Education for civic reasoning and discourse should be taught through project-based, inquiry-oriented curricula and practices.

- Learning to engage in civic reasoning and discourse should explicitly include strategies to help students gather, analyze, and thoughtfully circulate information in digital and other media, including identifying and combating misinformation

- All of the core subject areas can contribute to the range of knowledge, skills, and dispositions that students need to develop in order to investigate problems that emerge in the public domain.

- Teachers and administrators should be prepared to create high-quality civic learning opportunities that build on the strengths and experiences of students and take students’ developmental needs and trajectories into account.

Civic Engagement at NYKids’ Positive Outlier Schools

As we noted in previous blogs, NYKids’ studies of positive outlier schools found that educators emphasized civic engagement in their pedagogies.

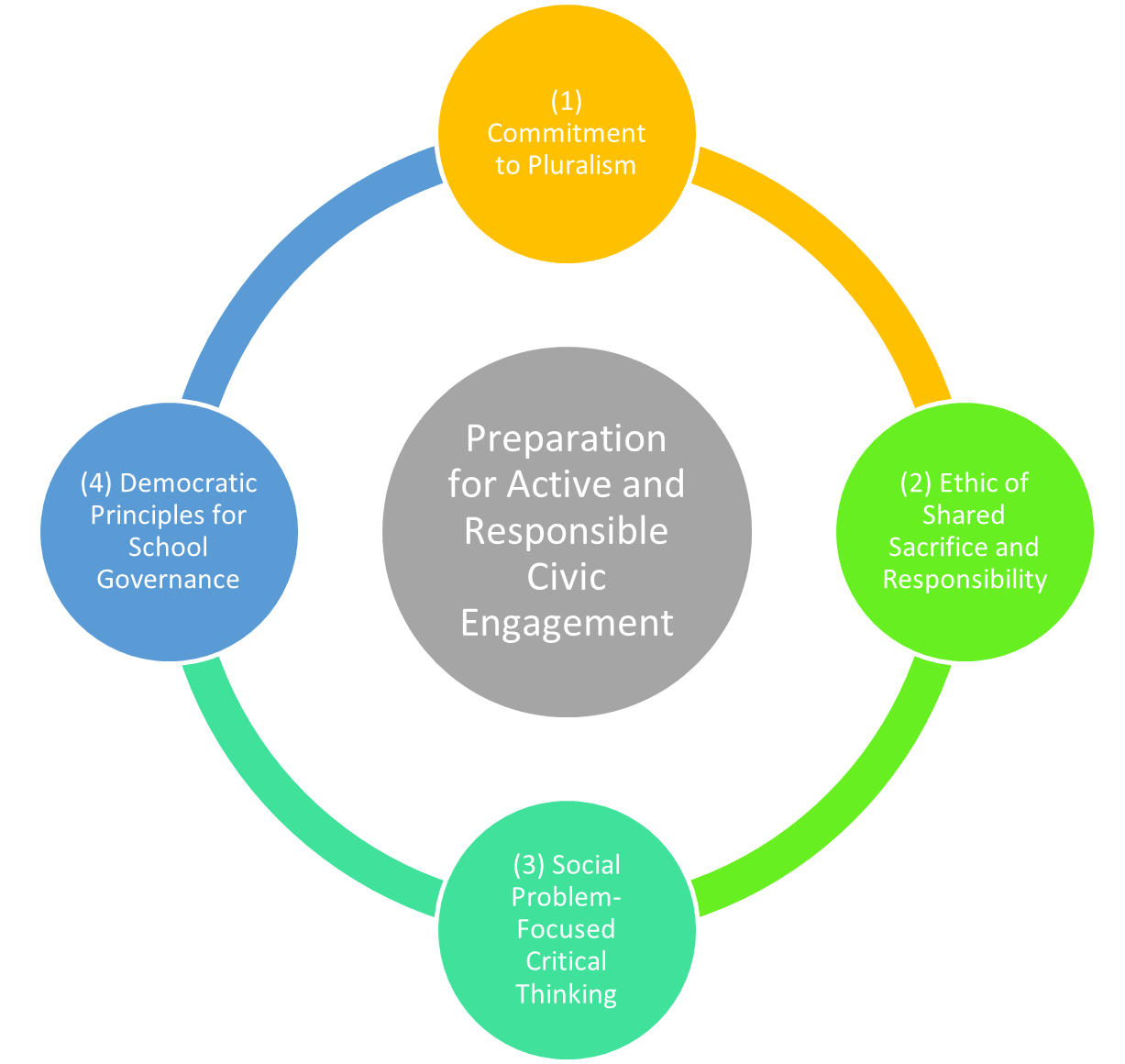

In particular, we found four distinguishing practices in positive outlier schools outlined below and attested to by students:

- 1) Commitment to Pluralism: Educators communicated a commitment to pluralism by celebrating diverse perspectives, abilities, and identities across the school community.

“I feel like everyone here acts their own way. We’re all different. We all express ourselves differently so it’s like they don’t really label us to be someone. The school really makes ourselves come out more – who we are, instead of putting a label on us or what we should do in life.” – Crown Point student

“I feel like everyone here acts their own way. We’re all different. We all express ourselves differently so it’s like they don’t really label us to be someone. The school really makes ourselves come out more – who we are, instead of putting a label on us or what we should do in life.” – Crown Point student

- (2) Ethic of Shared Sacrifice and Responsibility: Educators set expectations and standards for student conduct and behavior, which were intended to foster a reciprocal relationship of trust and mutual respect between individuals and the community. This focus was based on the belief that individual benefits such as “belongingness” accrue when there are expectations set forth for students to be responsible for something greater than themselves. For instance, students were encouraged to develop a sense of ownership for how their individual actions impacted the wider community.

“Malverne is a small school, so I mean – especially if you’re here for four years, you basically know a lot of people here and you have connections. . . . Everyone is like supportive of each other. I mean, once you know everyone here it’s like they’re kind of just your family.” – Malverne student

- (3) Social Problem-Focused Critical Thinking: Educators identified critical thinking as key to encouraging students to become responsible citizens who can navigate complex social problems. In particular, educators noted the ways in which modern society places new demands and responsibilities on classroom teachers to include opportunities for robust discourse around social problems where students explore a range of views rather than ascribing to insular viewpoints or take on reactive stances.

“So for every class, the school meets your needs. If you want to be a doctor, if you want to be a lawyer or a professional swimmer – it doesn’t matter. The school right now has so many activities and stuff that, even if you don’t have a specific class that suits your needs, you have clubs and activities and events that just spark your interest. And then it gets you prepared for other things that you might do outside of high school.” – Malverne student

- (4) Democratic Principles for School Governance: Unlike at typically performing schools, where hierarchical approaches to governance were dominant, educators at positive outlier schools embraced democratic principles for school governance. A distinguishing feature of positive outlier schools in this regard was the acknowledgement that a communal approach to leadership where students, parents, and families were brought into formal governance processes could deliver important benefits to the school community.

“There are going to be a lot of situations where you have more choices. Instead of being told just what to do, you’ll have to think out-of-the-box and figure out something, a different way to do something or another way of expressing an idea. I think that having a lot more freedom of how you want to do things kind of helps you prepare for that.” – Crown Point student

Future Directions

Policymakers will play an important role in ensuring that civic education is prioritized in in U.S. classrooms. To this end, the NAEd report authors suggest that schools require government courses to be taught in all middle schools and high schools. Moreover, states and districts should build on students’ strengths and experiences in designing “project-based, inquiry-oriented curricula.” Federal, state, and local governments must also work to ensure that adequate resources and funding are provided to develop and implement high-quality civics education.

To continue this important work, NAEd will hold more webinars about civics education and partner with local communities and key stakeholders to implement the suggested practices.

We encourage you to read visit our webpage to read case studies of the positive outlier schools highlighted in this blog. We also have posted resources to support civil discourse and civic engagement lesson planning. Please reach out to us with comments and questions at nykids@albany.edu as well as to sign up for summer professional development opportunities drawing on NYKids research at this link.