Celebrating Independence Day with a Grand Vision for Public Education

by Aaron Leo

As Independence Day approaches, we take the opportunity to reflect on the potential for education to fulfill the promise of democracy and equality laid out by the architects of the United States Constitution. This blog explores the democratizing vision of schooling promoted by progressive reformers and the challenges faced by educators in meeting fulfilling this dream. Despite persistent educational gaps, culturally relevant and critical approaches to education offer great promise for progressive education in the 21st century.

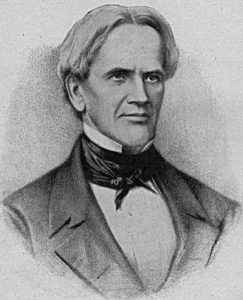

Public Schools as “The Great Equalizer”

The great 19th-century progressive school reformer Horace Mann famously referred to the school as “the great equalizer” of society and campaigned to ensure that all students had access to a quality education. Several decades later, philosopher John Dewey argued that schools should prepare students for active participation in democratic society by offering curricula and pedagogy which are intimately connected to their social lives.

However, by the 20th century, it became clear that schools were not delivering on their promise of equalizing society as wide gaps across lines of class and race were proving persistent and difficult to close. So clear were these inequalities that a group of critical scholars in the 1970s began to question the meritocratic nature of schools and the role they played in a hierarchical society.

However, by the 20th century, it became clear that schools were not delivering on their promise of equalizing society as wide gaps across lines of class and race were proving persistent and difficult to close. So clear were these inequalities that a group of critical scholars in the 1970s began to question the meritocratic nature of schools and the role they played in a hierarchical society.

These scholars and educators – arguing from the theory of Social Reproduction – provided evidence that students from different class and racial backgrounds were treated differently in schools and that unequal educational outcomes were often drawn sharply along these lines. From this perspective, schools are not sites of equality but institutions which actually reproduce the existing inequities in society by rewarding students already in privileged positions while disadvantaging others.

Progressive Education in the 20th Century

While educational inequalities have continued to persist, many have disputed the deterministic tenor put forth by Social Reproduction theorists. Calling attention to student and teacher agency and the emancipatory potential of education, several strands of scholarship promoted pedagogical strategies for educators seeking social transformation. Rooted in Brazilian educator Paulo Freire’s philosophy of education, Critical Pedagogy argued for educators to center their teaching around issues of power, inequality, and critique as means to develop a critical consciousness in their students. From a slightly different perspective, Culturally Responsive Education has emerged as a set of strategies and pedagogical attitudes designed to recognize and build from the resources and knowledge students of color and other marginalized students bring to schools.

These approaches, though stymied by recent reforms which promote accountability-focused behaviors that perpetuate poor learning opportunities for many young people, have proved effective strategies for closing achievement gaps and empowering marginalized youth as well as their teachers.

Disrupting Social Reproduction at Odds-Beating Schools

For over two decades, our NYKids team has conducted research on schools which have worked to fulfill the equalizing potential originally laid out by Mann. In our most recent project, we studied seven high schools which had better graduation outcomes among their economically disadvantaged and African-American, black, Hispanic, Latino, and English language learner students than predicted by statistical models. Though different in their community ecologies and student populations, these schools shared four themes in common which they attributed to their odds-beating outcomes.

For over two decades, our NYKids team has conducted research on schools which have worked to fulfill the equalizing potential originally laid out by Mann. In our most recent project, we studied seven high schools which had better graduation outcomes among their economically disadvantaged and African-American, black, Hispanic, Latino, and English language learner students than predicted by statistical models. Though different in their community ecologies and student populations, these schools shared four themes in common which they attributed to their odds-beating outcomes.

1) Co-Construction a Humanizing School Community

Often describing their school community as a “family,” educators at odds-beating schools emphasized relationship building across all levels, recognized the contributions of all schools staff, and facilitated youth-driven identity development with the goal of developing well-rounded students prepared for life after high school.

“Everyone is close and supportive. I have never felt like I was alone at any time on any issue, whether it is an educational issue or a personal issue. The support here is phenomenal.”

– Crown Point teacher

2) Collaboratively Defining and Achieving Success

Leaders, teachers, and student-support professionals at odds-beating high schools expressed the belief that they cannot “go it alone” if they are to reach their high aspirations for the young people they serve. To this end, educators at odds-beating schools defined success as more than meeting external targets established by others and collaborated to find promote solutions to problems they identified at their schools. In this process, odds-beating educators worked to actively engage parents and family members.

“It’s that team approach. If you work in isolation, you’re only serving yourself. It’s all in that connection.”

– Sherburne-Earlville principal

3) Cultivating Culturally Responsive, Inclusive, and Facilitative Leadership

Leadership at odds-beating schools is characterized by mutual trust and collaboration among staff members and a shared sense of responsibility for nurturing the general well-being of all young people. School and district leaders worked to hire and develop culturally responsive staff members, interacted with staff members to identify and solve problems, and network with other educators while maintaining a shared vision of success.

“We put a tremendous effort into the hiring process. We need to hire the right people for the job. You have got to love kids. You have got to have a genuine love for children. I can teach you how to teach if you have a passion for it, but you have to love kids.”

– Malverne principal

4) Customizing Innovative Programs and Practices

Educators at odds-beating schools frequently described pedagogical goals in terms that emphasize critical thinking, civic participation, and preparation for college and career that go beyond standard measures of high school success, such as graduation rate or state exam scores. These schools offered a wide range of programs and courses designed to develop students into well-rounded and productive members of society.

“I hope [a graduate is] someone able to adapt to changing times and changing technology and able to think critically and think for themselves and adapt to changes in the world and changes in careers that are out there.”

– Maple Grove school leader

See the cross-case report that can be used as a book study with students, parents, teachers, other school staff, and leaders or join one of our upcoming continuous improvement sessions (COMPASS) with your improvement team by reaching out to nykids@albany.edu.

Thank you for following NYKids’ News and liking us on Facebook and connecting on Twitter.