Better Relationships – Better Decision-Making – Better Outcomes for Students and Educators

By Manya C. Bouteneff, Ed.D.

Poverty is not fate. The cycle of poverty and poor academic performance is not inevitable. I identified high-poverty, non-selective public schools in New York State where Economically Disadvantaged (ED) students do well according to rigorous performance criteria, then undertook to learn to what practices the leaders of these schools attribute their success.

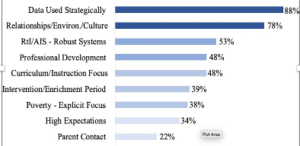

Coding notes from interviews with 164 successful schools’ principals uncovered the two practices they saw as key to leading school turn-around and high achievement for ED students: using data strategically and building relationship and culture.

These two approaches, using data strategically, and building relationship and culture, were far and away the most frequent practices described as key both in elementary/middle schools, and in high schools. Moreover, we learned that these practices did not require additional funding or staff; most of the principals we interviewed used existing resources and shifted the focus of existing staff meetings to achieve their success.

Data, Relationships, and Culture

So, what does it mean to use data strategically, and to create relationships and positive culture?

To use data strategically, the successful leaders we interviewed used a variety of data types: quantitative data such as attendance or test results; anecdotal or qualitative data such as writing-prompt responses or perceptions of safety. They also used a variety of home-grown methods for analyzing the data. What they had in common was a continuity of purpose and stick-to-itiveness. They became increasingly successful and used academic data with enough granularity that, as many of them said, “it’s like every student here is on an IEP.” They and the teachers knew where each student was, and where they needed to move. They did not give up trying new ways to get them there.

Creating relationships and positive culture was achieved in as many ways as there were principals we spoke to! For example, school leaders and staff learned students’ names and greeted them each morning, mentors were assigned to students without home support to check in with them each day, prevention overtook punishment, and each student had a place as a member of the school community. Staff were treated with respect and became an integral part of the turn-around effort, feeling increasingly proud and empowered. The leaders we spoke to often said something like, “please, come visit, you will feel like you are walking into a family.”

Creating relationships and positive culture was achieved in as many ways as there were principals we spoke to! For example, school leaders and staff learned students’ names and greeted them each morning, mentors were assigned to students without home support to check in with them each day, prevention overtook punishment, and each student had a place as a member of the school community. Staff were treated with respect and became an integral part of the turn-around effort, feeling increasingly proud and empowered. The leaders we spoke to often said something like, “please, come visit, you will feel like you are walking into a family.”

“But, what about… ?” Your hearts and training may have you arguing for any number of other practices right now. Let’s use parent involvement as an example. Parent involvement appeared eighth on the list of the top ten keys in the Elementary/Middle school study, and nowhere on the top ten in the High-School study. So, are these principals for real? How can they ignore parents?

The vital thing we learned from principals whose results prove that what they do works, is that we need to temporarily set aside many things we’ve heard about successful schools, and start with a focused approach, focused practices. Focus on using data strategically to move each student forward academically and socially, and focus on creating relationships and a safe and welcoming environment for teachers and students. The principals in our study used data and relationships to access and turn around every aspect of the school, one after another. Remember, their results speak for themselves.

Stabilizing Before Initiating Large-Scale Changes

Just as a doctor responding to a patient with a heart attack will not attempt to change the patient’s diet, exercise, and smoking habits in the emergency room, so must we focus first on vital signs and stabilizing our “patient.” Save introducing other healthy practices for later.

“OK,” you say reluctantly, “I get it” but you may be wondering HOW you can use data strategically, or HOW you can achieve a positive culture. In fact, you may fear you lack the necessary capacity in your building to do so. No one ever feels ready, no one believes they have full capacity, the time is never just right. Just start!

To quote Reeves (2013), focus on “practices, not programs.” Go home-grown! Most of the leaders we spoke to did. If you feel intimidated, start by doing what some of our successful principals did: look at something that is less intimidating for you and your staff. Many of the principals we spoke to started with responding to student behavior issues. What about collecting data on behavior infractions at your school: which are most frequent? at what time of day do they occur? where? Then, with relevant stakeholders, use the data to plan preventative interventions, remeasure, and celebrate.

In such ways, you will be using data strategically in ways that have a direct impact on empowering, not blaming teachers or students. When that “data barrier” is crossed, you can start using data to address academic struggles. Create your own systems and timelines for data meetings and check-ins. Over time, you and your teams will get good at this, will start to see successes, will begin to see this work as deeply satisfying, and will get increasingly granular. Most important with any data use, many of our principals told us, is to set the expectation of no blame – not for teachers, not for students, not for parents – the only focus is a determined curiosity and experimentation until we know what will work for each student. That is part of creating relationships and positive culture.

Am I making this sound too easy? Having turned around two schools myself, I know that this is a challenging and courageous road to take. I bear scars and most of the principals we spoke to do as well. However, while we may regret missteps we made along the way, none of us regret adopting the practices that helped us beat the odds and built opportunities, pulling students out from what may seem like the inevitable cycle of poverty, repairing the poor self-image resulting from poor performance, and debunking the prejudice that gets reinforced when certain “types” of kids do badly in school and then in life. You have the power to do that, too. Please, just start!

Am I making this sound too easy? Having turned around two schools myself, I know that this is a challenging and courageous road to take. I bear scars and most of the principals we spoke to do as well. However, while we may regret missteps we made along the way, none of us regret adopting the practices that helped us beat the odds and built opportunities, pulling students out from what may seem like the inevitable cycle of poverty, repairing the poor self-image resulting from poor performance, and debunking the prejudice that gets reinforced when certain “types” of kids do badly in school and then in life. You have the power to do that, too. Please, just start!

No, indeed, poverty is not fate. The cycle of poverty and poor academic performance is, indeed, not inevitable.

We thank you for your interest in NYKids! Please keep up with our latest news by following us on Twitter, Instagram, or Facebook. You can also read our latest research on our website or contact us with feedback at nykids@albany.edu.

You can learn more about Dr. Bouteneff’s work on her website Better Outcomes Research and contact her through LinkedIn and her Monroe College email (mbouteneff@monroecollege.edu).