An Ecological View of Rural Student Aspirations

By Aaron Leo & Kristen C. Wilcox

The American Educational Research Association’s Annual Meeting occurred over the past week in a virtual format due to the pandemic. As we described in last week’s blog the AERA annual meeting brings together policymakers, researchers, and educators from around the globe to share research findings, connect with each other, and make progress toward improving educational opportunities for people of all ages around the world. This blog shares a NYKids AERA presentation based on our most recent study and highlights our analysis on rural students’ aspirations along with a summary of other presenters’ work.

The session in which our NYKids team participated included a number of exceptional research papers all focused on students’ educational experiences in rural communities.

The first paper entitled “A Quantitative Study in the Black Belt: Measuring Performance and Exploring Black Rural Education” was given by Tonya Perry, Samantha Elliott Briggs, and Donna Turner. Their paper focused on their research in Alabama in what the paper authors describe as “the black belt”. This region of Alabama was the center of the wealthiest cotton plantations and is now one of the “poorest stretches of land in the United States”, according to the authors.

These authors investigated absenteeism, grades, and behavioral incidences. Like our NYKids team, their researchers drew on a social-ecological framework that takes into account the different contextual influences on youth outcomes. They found that “absences and behavior impact students’ grades” and they analyzed the degree of impact using a quantitative design, looking to identify how and why these absences and behavior exist through qualitative methods. A shared perception of “…not belonging in school spaces” was just one of the findings from their focus groups with students.

These authors investigated absenteeism, grades, and behavioral incidences. Like our NYKids team, their researchers drew on a social-ecological framework that takes into account the different contextual influences on youth outcomes. They found that “absences and behavior impact students’ grades” and they analyzed the degree of impact using a quantitative design, looking to identify how and why these absences and behavior exist through qualitative methods. A shared perception of “…not belonging in school spaces” was just one of the findings from their focus groups with students.

Overall, they found that individual, interpersonal and community, and institutional and policy factors are all working on students “at the same time”, so no one factor is at play in explaining absenteeism and behavioral incidences. In sum, these authors point to the resilience of the students in this community, the strengths of the diversity of their community (likened to a “nice hot pot of gumbo”), and the importance of coming to know who students are on a personal level.

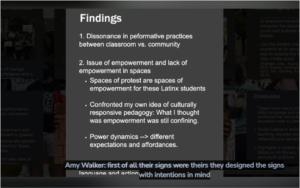

Next, researcher Amy Walker presented her paper entitled “Standing with my students: A reflexive examination of youth activism in rural communities”. In this paper the author used autoethnography (a method in which the researcher is both reflexive and reflective about the subject of inquiry and her subjectivities in telling the stories of others). The paper recounted the activist roles taken by three Latino/a students in a rural community in response to such events as the George Floyd killing. The students’ enthusiasm and activism in relation to these events stood in contrast to the more passive positioning they tended to take in their classrooms. The author noted how this dissonance between their affect and behaviors inside and outside of the classroom reveals “power dynamics… that relate to different expectations and affordances” for their participation.

Next, researcher Amy Walker presented her paper entitled “Standing with my students: A reflexive examination of youth activism in rural communities”. In this paper the author used autoethnography (a method in which the researcher is both reflexive and reflective about the subject of inquiry and her subjectivities in telling the stories of others). The paper recounted the activist roles taken by three Latino/a students in a rural community in response to such events as the George Floyd killing. The students’ enthusiasm and activism in relation to these events stood in contrast to the more passive positioning they tended to take in their classrooms. The author noted how this dissonance between their affect and behaviors inside and outside of the classroom reveals “power dynamics… that relate to different expectations and affordances” for their participation.

Finally, in our paper “Toward a culturally-responsive education”, we described some of our findings from NYKids’ most recent College and Career Readiness study, which drew upon focus groups and interviews with 11 juniors and seniors in Crown Point— a rural positive outlier school. In this paper we focused on youths’ aspirations for life after high school. Utilizing an ecological framework, we shared the following findings:

- Families and educators were the most prominent influences on rural youths’ aspirations. These included siblings and grandparents, not just parents.

- There was little evidence of antagonisms between school employees and family members or pressure to pursue post-secondary education (instead of enter the workforce or military directly after graduation) or to leave the community to fulfill their aspirations. Instead, considering many different pathways was encouraged.

- Community attachment was increased through service projects encouraged by school staff and feelings of community pride contrasted with deficit views about their own or other rural communities.

After the presentations, the panel of researchers ended by discussing the following question:

What might K-12 and higher education learn from rural communities?

In terms of student voice, the researchers noted that for many years there has existed a tendency to proscribe narratives on rural communities and rural community members in deficit ways. However, using research methods that lift up voices of youth in rural communities can help us to see and hear them as active agents in visioning their own lives and the futures of their communities. This approach can help mitigate the tendency to “homogenize” rurality and approach the rural student educational experience from an asset perspective.

In terms of student voice, the researchers noted that for many years there has existed a tendency to proscribe narratives on rural communities and rural community members in deficit ways. However, using research methods that lift up voices of youth in rural communities can help us to see and hear them as active agents in visioning their own lives and the futures of their communities. This approach can help mitigate the tendency to “homogenize” rurality and approach the rural student educational experience from an asset perspective.

For more about Crown Point see a case study or our most recent cross-case report on our webpage. Our entire AERA presentation can be found here as well.

Also, if you are interested in direct support in using NYKids research and our continuous improvement processes, please sign up for upcoming workshops and improvement institutes being offered in collaboration with Capital Region BOCES. We will be offering workshops on “Building capacity for continuous improvement” on May 4th (one session from 9-11am and another 1-3pm). For more information please go to the MyLearningPlan and sign up today.

As always, we welcome your feedback and any questions you might have about our research or direct continuous improvement support at nykids@albany.edu.